Overview — Oceanography and Bathymetry

Table of Contents

Oceans, Seas, and Basins

The Gulf of Mexico covers more than 1.6 million km² (617,000 mi²); approximately 1,770 km (1,100 mi) at its widest point and 1,287 km (800 mi) at its longest point. It consists of large continental shelves that extend for some 320 km (200 mi) along the west coast of Florida and the Yucatan coast, the continental slope, and the abyssal plain in the center.

The Caribbean Sea is about 2.8 million km² (1.06 million sq. miles), nearly twice as large as the Gulf of Mexico. It is about 3,058 km (1,900 mi) from Central America to the Leeward Islands. In the northwest Caribbean there are the Yucatan and Cayman Basins. The Colombian and Venezuelan Basins occupy most of the central Caribbean, with the smaller and shallower Grenada Basin in the east.

The narrow and steep Cayman Ridge separates the Yucatan and Cayman Basins. The Nicaraguan Rise, a triangular-shaped ridge that extends from Central America towards Hispaniola, separates the northwest Caribbean from the rest. The Beata Ridge runs north-south between the Venezuelan and Colombian Basins, while the Aves Ridge separates the Grenada Basin from the rest of the Caribbean Sea.

The Campeche Bank is an extension of the Yucatan Peninsula into the Gulf of Mexico. The Gorda Bank is the shallow region connecting Central America and the Nicaraguan Rise. The Great Bahama Bank encloses the Bahamian islands and separates Cuba from the deep Atlantic Ocean to the east.

Prominent Trenches and Straits

The deepest part of the Caribbean Sea is the Cayman Trench (the Barlett Deep), which lies between Cuba and Jamaica. It is approximately 7,686 m (25,216 ft) below sea level. By comparison, the deepest part of the Gulf of Mexico, the Sigsbee Deep in the southwest, is about 4,000 m (13,000 ft) deep. On the edge of the northeast Caribbean is the Puerto Rico Trench, the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, at 8,648 m (28,374 ft) below sea level.

The Yucatan Channel connects the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, while the Straits of Florida, between Cuba and Florida, allow water to flow between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic.

Moving east from Cuba, we arrive first at the Windward Passage, which separates Cuba and Hispaniola. Between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico lies the Mona Passage. Farthest east is the Anegada Passage, which separates the Virgin Islands from the Lesser Antilles. Between the Venezuelan Basin and the Colombian Basin is the Aruba Gap, which has depths greater than 4,000 m (13,000 ft).

Major bathymetric features are associated with plate tectonics. For example, the Cayman Trench is a divergent region between the Caribbean Plate and the North American Plate.

Mean Sea Surface

Mean Sea Surface Sea Surface Temperature (SST)

The SST is controlled mainly by the solar heating cycle, so the mean SST declines from equator to poles and the range increases. Consequently, the most dramatic seasonal change occurs in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

While SST isotherms are primarily zonal, relatively strong gradients occur along the coastal boundaries of the Gulf of Mexico, consistent with the differential heating between land and ocean and between deep and shallow waters. For example, during winter SSTs near the coast of Florida are relatively low compared with SSTs at the same latitude in the open waters of the Gulf. Pockets of relatively low SSTs occur along the coast of South America, the Campeche Bank, and shallow shelves of the Greater Antilles, the result of frontal passages and local winds such as land breezes that move waters away from shore and cause coastal upwelling. Relatively low SSTs in the Gulf of Tehuantepec, on the Pacific coast of southern Mexico, are the result of frequent episodes of strong northerly winds from the Gulf of Mexico that cause strong cold upwelling.

The highest SSTs occur over the Gulf of Mexico and the northern Caribbean during summer in response to solar heating and surface water piling up in the western basin in response to wind stress from the easterly trade winds.

Sharp gradients of SST around Florida and the Gulf of Mexico during winter, spring, and autumn are useful for defining current structure. However, during summer, SST is not useful for defining current structure as the temperature gradients weaken over the Gulf and Caribbean Sea.

Mean Sea Surface Salinity

Salinity is strongly influenced by river outflow (which is seasonal and episodic), evaporation, and freshening from precipitation. Not surprisingly, salinity is lowest and gradients are strongest in the northern Gulf and the southeastern Caribbean, areas that receive large fresh water discharge from the Mississippi and Orinoco, respectively. In general, a region of high salinity extends from the Atlantic to the southern Gulf of Mexico and the northern Caribbean, which has the smallest annual salinity range. The region of maximum salinity is farthest north during winter, a time with a correspondingly narrow strip of steep gradients around the Mississippi estuary. For the Caribbean Sea, the highest mean salinity and weakest salinity gradients occur during spring.

Salinity is at its lowest over the Gulf of Mexico during summer when the river discharge is highest, as expected from seasonal rainfall and snow melt in the north. For the Caribbean Sea, the salinity is at a minimum in autumn, a result of high river discharge into the tropical Atlantic.

Mean Sea Surface Waves

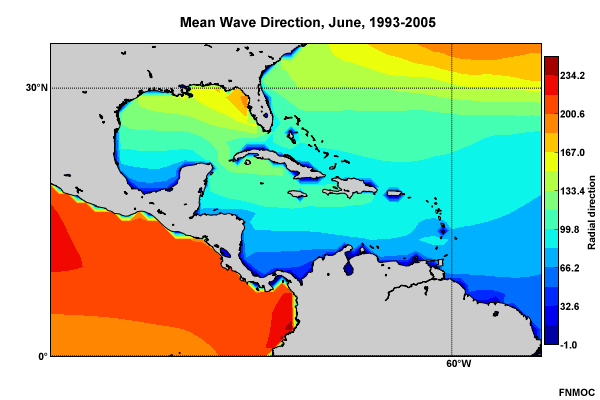

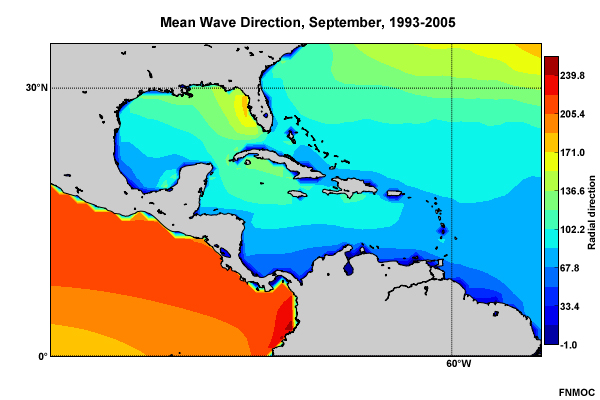

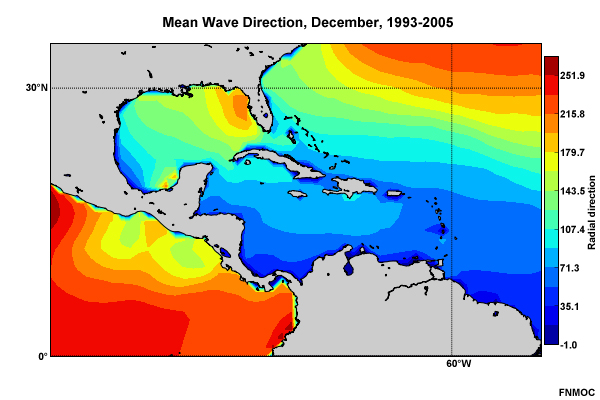

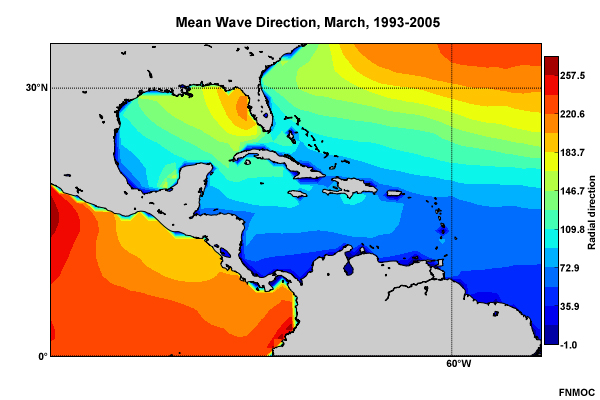

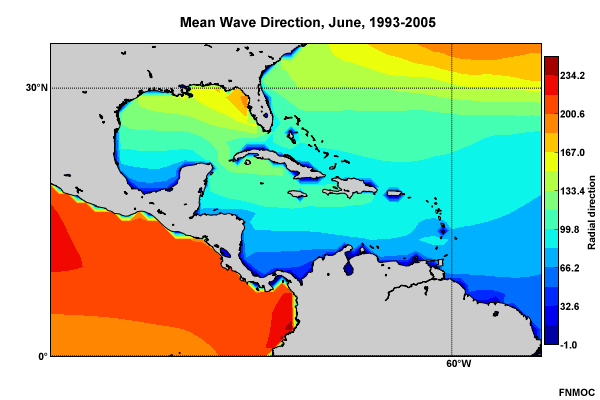

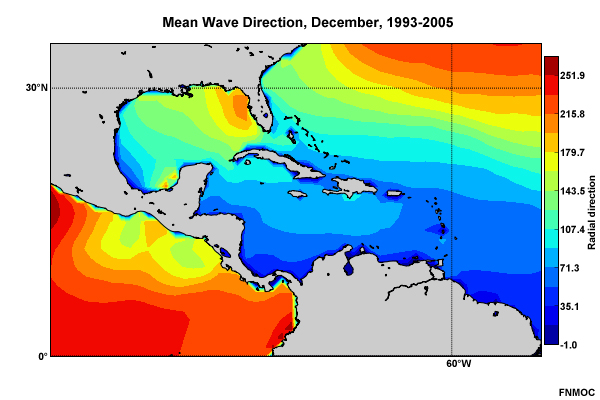

Mean Sea Surface Waves - Wave Direction

June

September

December

March

Waves are primarily driven by winds so the annual cycle of the mean wave direction (Tabs 1-4) reflects the large-scale surface circulation in the atmosphere.

The Bermuda-Azores High is dominant during the summer. Therefore, wave directions are northeasterly to southeasterly over the Caribbean and southern Gulf of Mexico and mostly southerly to south-southwesterly along the West Florida Shelf.

The eastward shift in the center of the Bermuda-Azores High during winter results in the mean wave direction in January becoming more southerly and southwesterly over most the Gulf. Notice the pockets of northeasterly wave direction in the southwestern Gulf as well as in the Gulf of Tehuantepec on the Pacific coast of southern Mexico. The wave direction in those areas indicates the influence of intruding high pressure and northerly winds in the wake of cold fronts. Across the southern and central Caribbean, wave direction is mostly northeasterly to easterly during winter, a response to the eastward migration of the high pressure center over the Atlantic.

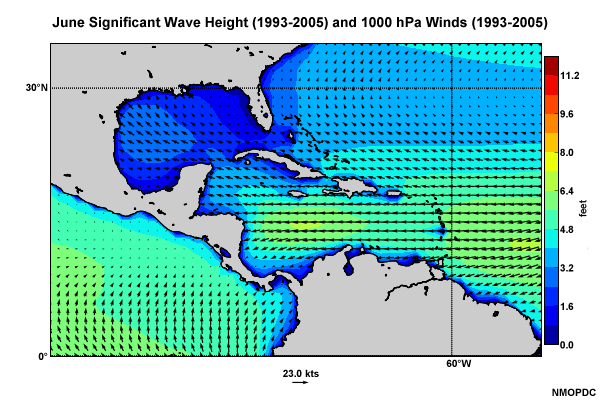

Mean Sea Surface Waves - Winds and Significant Wave Height

June

December

March

September

In general, significant wave heights are higher over the Caribbean than the Gulf of Mexico—a reflection of the stronger mean surface winds (Tabs 1-4). For the region as a whole, significant wave heights reach a maximum during winter (December) and minimum during autumn (September). The regional maximum is in the southwestern Caribbean Sea beneath strong easterly and northeasterly trade winds. Significant wave heights are relatively low in the near Gulf coast, particularly the West Florida Shelf and Bay of Campeche during all seasons. Low significant wave heights are also along the south coasts of the Greater Antilles and over the southern Lesser Antilles during autumn. Local minima occur in bays along the coast of South and Central America.

Notice the dramatic changes over the Gulf between winter and summer. During summer, significant wave heights drop to about one foot over the eastern and southern Gulf and the maximum shifts to the northwest Gulf in response to southeasterly winds. During winter, significant wave heights are at a maximum over the central Gulf, reaching near five feet.

Synoptic systems such as hurricanes, fronts, and surges in the trade winds can cause short-term shifts in the wave direction and significant changes in wave heights.

Major Currents

Currents are defined by their temperature and salinity characteristics. In general, large-scale currents in the western tropical oceans are warmer than the eastern currents because the prevailing winds cause piling of warm waters in the west and upwelling of cooler deep water in the east. For example in the tropical Atlantic, the Gulf Stream and North Equatorial Currents are warm, while the Canary Current is cool.

Surface Current

Surface Current over Speed

The Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean can be divided into major currents regimes including the Caribbean, Yucatan, Loop Current, Florida Current, which feeds into the Gulf Stream of the Atlantic, and the Antilles Current, which flows east of the Bahamas. Connecting these current regimes are waters flowing through the major channels, passages, and straits discussed earlier. Non-typical currents can be created by wind shifts that occur under different synoptic weather regimes, such as frontal passages.

Large-scale Tides

The Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean region experience small mean tidal ranges, from 90 cm (3 ft) in the northern Gulf to less than 20 cm (0.7 ft) in the southern Caribbean. Diurnal tides are experienced in the Gulf of Mexico along the western and southern boundaries, as well as in the Mississippi Delta region. Elsewhere, the region experiences a mixture of diurnal and semidiurnal tides.

Questions

Questions Question 1

Complete the following sentence. The Mona Passage is between _____: (Choose the best answer.)

The correct answer is d.

Questions Question 2

The deepest water in Caribbean Sea is found in the: (Choose the best answer.)

The correct answer is d.

Questions Question 3

Use the selection box to choose the answer that best completes the statement.

Questions Question 4

Use the selection box to choose the answer that best completes the statement.

Questions Question 5

SST gradients are useful for defining current structure during summer in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

The correct answer is False.

Questions Question 6

In general it can be said of mean salinity in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean that: (Choose all that apply.)

The correct answers are a and b.

Salinity is lowest and gradients are strongest in the northern Gulf and the southeastern Caribbean, areas that receive large fresh water discharge from the Mississippi and the Orinoco, respectively. It is highest in the northern Caribbean and southern Gulf, the regions with the smallest annual range in salinity.

Questions Question 7

Below is the properly labeled image:

Questions Question 8

Use the selection boxes to choose the answers that best completes the statement.