Introduction

Tsunami hazards differ from weather hazards in significant ways, requiring forecasters to be aware of the nuances in the warning process and best communication practices for decision support. These key differences include the following:

- A tsunami can affect coastlines all across an ocean basin, in some cases simultaneously affecting multiple locations separated by large distances.

- Because an earthquake (EQ) can immediately generate a tsunami, which travels very quickly, there isn’t always time to get a warning out to coastal communities nearest the source.

- The initial tsunami warning process requires focusing on what causes an event, because by the time there is evidence that a tsunami has been generated, it is often too late for a warning to reach those who are the first to be impacted. In this way, tsunami warning communication is different from warnings for some other types of natural hazards.

- The best science can detect and warn of a tsunami, but the role of personal responsibility in reacting to warning messages is also substantial. For example, people in areas near known tsunami source regions need to know how to recognize nature’s warning signs and take responsibility to get themselves to safety. In areas where a warning can be received, clear information from the Tsunami Warning Centers (TWCs) and Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs) will allow local authorities to make evacuation decisions and implement other actions that people can follow.

Good decision support for tsunami events relies on building effective partnerships with your decision-makers ahead of the event to ensure everyone understands tsunami hazards and the tsunami warning process. The TsunamiReady Program provides a framework for these partnerships by establishing guidelines that promote tsunami hazard preparedness and improve public safety before, during, and after tsunami emergencies. For more information on tsunamis and tsunami preparedness, check out the following COMET lessons:

- TsunamiReady: Guidelines for Mitigation, Preparedness, and Response

- Community Tsunami Preparedness, 2nd Edition

In this lesson, we’ll focus on impact-based decision support services provided by National Weather Service WFOs in the context of a tsunami event. At key times in the evolution of the event, we’ll practice interpreting official tsunami watch, warning, and advisory products to convey information that is relevant to various decision-makers.

Introduction » Supporting Decision-makers

Decision-makers are concerned about the general threat of a tsunami in their area, but often need location-specific threat information, too. They use three general steps to prepare for a tsunami event:

- initiate actions based on thresholds - the thresholds in a Tsunami Advisory (1-3 ft, 0.3-1 m) and Tsunami Warning (>3 ft, >1 m) trigger actions.

- plan for threats - predictions of tsunami impacts and their relative uncertainties are considered in planning for identified threats.

- prepare for impacts - decision-makers ready the community for potential impacts and execute actions according to the plan specific to their area of responsibility.

Question

True or False. During a tsunami event, forecasters in coastal Weather Forecast Offices should provide the best possible Tsunami Warning Center (TWC) information available at the time to decision-makers.

The correct answer is a.

Forecasters provide decision-makers with the best possible forecast at the time, including information about what is known and what is still being determined. For a tsunami event, this should include the information available as the event evolves, along with possible impacts, so that the spectrum of outcomes can be assessed to reveal acceptable margins of safety.

Remember, each location has a different critical threshold and timing requirement, so it’s important for you to understand the information needs of your decision-maker(s) to help ensure your messaging is effective when an event unfolds.

Typically, decision-makers ask the following questions during a tsunami event:

- Is the tsunami going to impact my coastline?

- When will the tsunami arrive at my coastline?

- How big are the tsunami waves going to be?

- How confident are you that these impacts will materialize?

They look for essential pieces of information to help inform their decisions and preparedness actions, as shown in the table below.

|

Essential Elements of Information |

||

|

Earthquake Information |

Tsunami Wave Information |

Expected Impacts |

|

|

|

Local emergency management communities have their own inundation maps to inform them on where evacuations need to occur in the event of a tsunami, and these can be found on the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program - Tsunami Maps webpage.

Introduction » TWC Product Alerts

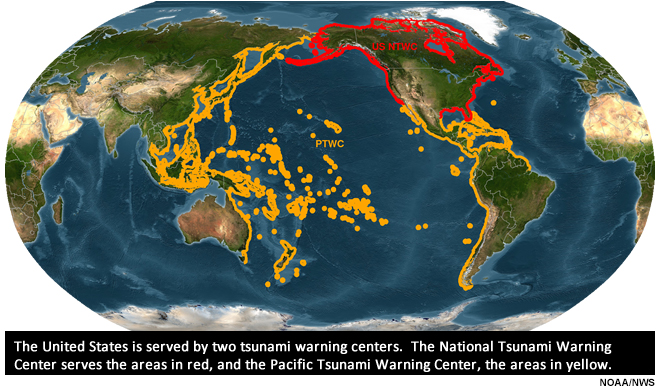

The U.S. has two Tsunami Warning Centers (TWCs):

- the National Tsunami Warning Center (NTWC) in Alaska, providing alerts and messages for Alaska, Canada, and the U.S. West, Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico coasts.

- the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Hawaii, providing alerts and messages for Hawaii, the Pacific Islands, and the Caribbean (Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, and British Virgin Islands). The PTWC also provides international tsunami advice in support of the UNESCO/IOC Caribbean and Pacific Tsunami Warning Systems (these products are not covered by this training).

The U.S. centers collaborate closely with the International Tsunami Information Center (ITIC). All alerts and messages can be found on a single-source website at tsunami.gov.

The TWCs have the goal of issuing an initial bulletin as rapidly as possible after a seismic event, within five minutes when possible. This initial product provides preliminary magnitude and location information for the earthquake that occurred, as well as the tsunami threat level. Initial messages can be tsunami warnings, advisories, watches, or information statements; these are intended to notify stakeholders, the public, and other decision-makers about the potential hazards associated with a tsunami-generating event.

The warning centers use criteria based on preliminary earthquake information (prior to tsunami detection) to determine when and where to issue the alerts. Additional seismic observations, water-level measurements, forecast models, and historical tsunami information are used to update subsequent alerts.

|

Alert Level |

Definition |

Potential Hazard(s) |

|

Warning |

A tsunami with the potential to generate wave heights >3 ft (>1 m) and widespread inundation is imminent, expected, or occurring. |

Dangerous coastal flooding and powerful currents |

|

Advisory |

A tsunami with the potential to generate 1-3 ft (0.3-1 m) wave heights and strong currents or waves dangerous to those in or near the water is imminent, expected, or occuring. |

Strong currents and waves dangerous to those in or very near water |

|

Watch |

A tsunami may impact the area of concern at a later time (in most cases, defined as more than 3 hrs). |

The potential tsunami hazard is not yet known/still being determined |

|

Information Statement |

An earthquake or other event has occurred of interest to the message recipients. |

No known threat or an event for which the hazard has not yet been determined |

Question

How is a decision-maker likely to respond based on the TWC alert that is issued? Use the pull-down menu to best match the alert to corresponding action.

The correct answers are highlighted above.

For more information about tsunami alert definitions and implications to the alert recipients, see the U.S. Tsunami Message Definitions.

It’s important to note that Watches, Warnings, and Advisories have a different use in tsunami situations than what you might be familiar with for weather situations. If an earthquake or other event occurs that may have generated a tsunami, a Warning or Advisory will be issued for locations within a 3 hour travel time, even without confirmation of a tsunami wave. It may not be known if a tsunami is occurring, but if tsunami waves were generated, nearby coastlines will be at almost immediate risk and people in harm’s way will need to take action based on the potential threat. For locations farther from the originating source, the initial product issued may be a Watch while the TWCs evaluate the potential threat, look for confirmation that a tsunami was generated, and assess whether areas farther from the originating source will be affected.

Once the primary danger associated with a tsunami has passed, a message will be issued canceling the tsunami alert. Official statements on when it is safe to return to coastal areas are left up to local emergency managers (EMs) because tsunami impacts and effects can vary dramatically along a coast. In the event of a major tsunami, other local dangers (debris, hazardous material spills, fires, etc.) may make the impacted area unsafe long after the tsunami threat is over.

For more information on the processes involved in anticipating, detecting, and warning for a tsunami, see the COMET lesson Tsunami Warning Systems.

Introduction » Local Information from WFOs

Local Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs) have many responsibilities during tsunami events, including but not limited to:

- Activating the Emergency Alert System (EAS) via NOAA Weather Radio for new or upgraded Tsunami Watches & Warnings

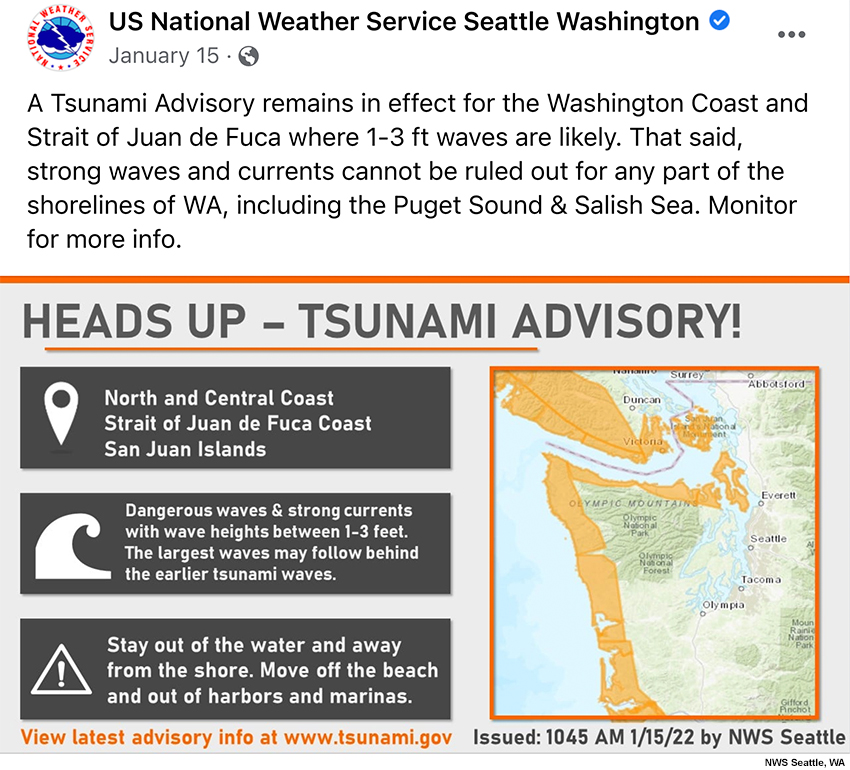

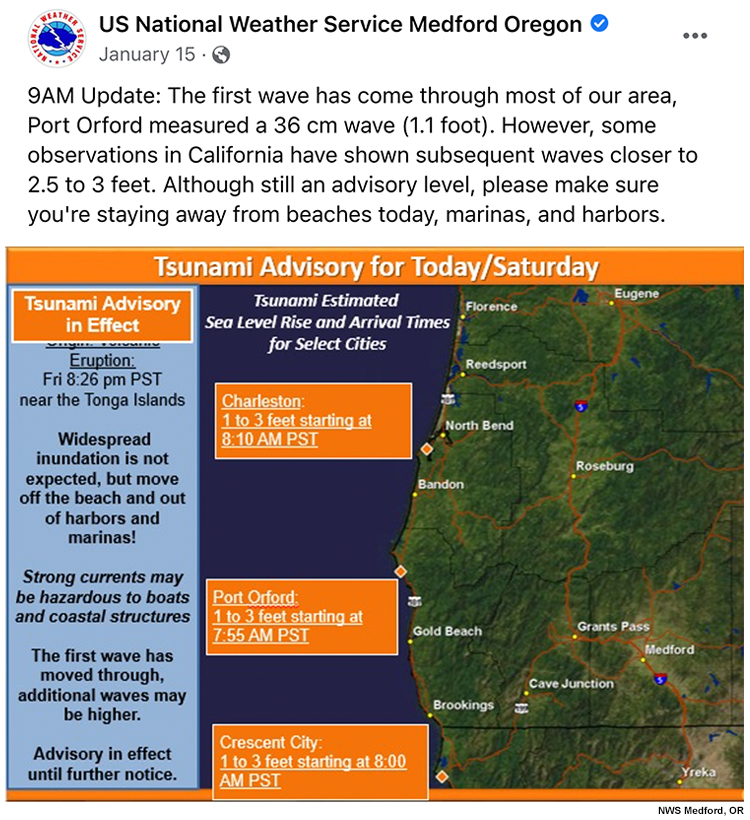

- Relaying Tsunami Watches, Warnings, & Advisories via NOAA Weather Radio and Social Media

- Transmitting Local Tsunami Information Statements & Marine Weather Statements according to local/regional procedures (see the example Local Tsunami Information Statement shown below)

- Providing Impact-Based Decision Support Services to state, county, local, and tribal partners. This includes TWC information, local tides, and significant weather information that could impact response actions

- Coordinating public information with local media partners

- Gathering and relaying real-time impact information to TWCs

- Assist in appropriate messaging via Beach Hazards Statements

- Support HAZMAT incidents as well as rescue/recovery operations

WFOs issue Special Weather Statements that include the tsunami alert level as well as location-specific tides and impacts information, as shown in the example below.

Special Weather Statement

National Weather Service Seattle, WA

532 AM PST Sat Jan 15 2022

...TSUNAMI ADVISORY IS IN EFFECT FOR THE NORTH AND CENTRAL

WASHINGTON COAST, STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA COAST, AND SAN JUAN

ISLANDS...

WAZ001-510-514>517-151645-

San Juan County-Admiralty Inlet Area-Eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca-

Western Strait of Juan De Fuca-North Coast-Central Coast-

Including the cities of Friday Harbor, Port Townsend, Sequim,

Clallam Bay, Joyce, Sekiu, Beaver, Clearwater, Forks, La Push,

Neah Bay, Ozette, Queets, Aberdeen, and Hoquiam

532 AM PST Sat Jan 15 2022

...TSUNAMI ADVISORY IS IN EFFECT FOR THE NORTH AND CENTRAL

WASHINGTON COAST, STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA COAST, AND SAN JUAN

ISLANDS...

* LOCAL IMPACTS...

A tsunami capable of producing strong currents that may be

hazardous to swimmers, boats, and coastal structures is

expected. Widespread inundation is NOT expected.

* RECOMMENDED ACTIONS...

If you are located in this coastal area, move off the beach

and out of harbors and marinas. Do not go to the coast to

watch the tsunami. Be alert to instructions from your local

emergency officials

* FORECAST TSUNAMI START TIMES...

Neah Bay Washington 0850 AM PST on Jan 15

Westport Washington 0850 AM PST on Jan 15

Moclips Washington 0855 AM PST on Jan 15

Port Angeles Washington 0930 AM PST on Jan 15

Port Townsend Washington 0955 AM PST on Jan 15

Tsunamis often arrive as a series of waves or surges which

could be dangerous for many hours after the first wave arrival.

The first tsunami wave or surge may not be the highest in the series.

* FORECAST PEAK TSUNAMI WAVE HEIGHTS... This information is still

being evaluated and determined.

* PRELIMINARY EARTHQUAKE INFORMATION...

An underwater volcanic eruption occurred at 827 PM PST on Jan 14

2022, centered near the Tonga Islands

* TIDE INFORMATION...

Neah Bay...Low tide of -0.3 ft at 603 PM PST on Jan 15. High

tide of 8.6 ft at 1027 AM PST on Jan 15.

La Push...Low tide of 0.1 ft at 529 PM PST on Jan 15. High

tide of 8.9 ft at 1018 AM PST on Jan 15.

Westport...Low tide of 0.3 ft at 527 PM PST on Jan 15. High

tide of 9.6 ft at 1035 AM PST on Jan 15.

Port Angeles...Low tide of -0.8 ft at 743 PM PST on Jan 15.

High tide of 7.5 ft at 1123 AM PST on Jan 15.

Port Townsend...Low tide of -0.9 ft at 837 PM PST on Jan 15.

High tide of 9.3 ft at 521 AM PST on Jan 16.

Friday Harbor...Low tide of -0.9 ft at 926 PM PST on Jan 15.

High tide of 8.4 ft at 551 AM PST on Jan 15.

This product will be updated as new information becomes available.

Stay tuned to your local news source and NOAA weather radio for

further information and updates.

Additional information can be found at

http://www.tsunami.gov

www.weather.gov/seattle

Tsunami Event Exercise

In the following exercise, you are in the role of a WFO forecaster addressing communications during various stages of a fictional tsunami event. This simplified fictional scenario represents select times during the evolution of a tsunami event. At each of these times, you will see the latest products from the TWCs providing an overview of the situation. You will be able to get an idea of how an event and the messages evolve over time, and will practice interpreting TWC products to field questions from emergency officials and other decision-makers.

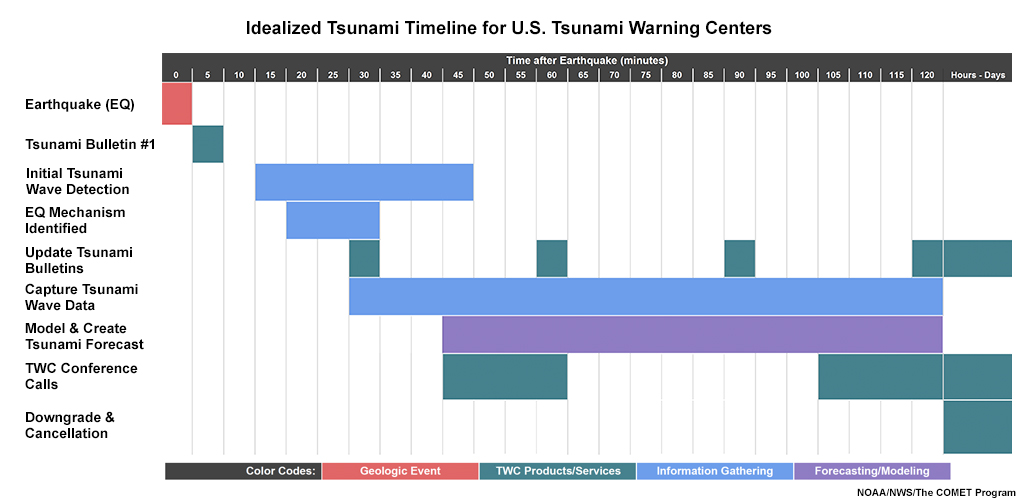

The timeline below will be used to note where you are in the event timeline relative to the geologic event and provide context for updates to observations, forecasts, and TWC product issuances. This idealized timeline represents a generalized sequence and timing for TWC analysis and communications during any given tsunami event.

Note that when stating earthquake magnitudes, the nomenclature is MX.X, where “M” is magnitude and “X.X” is the value expressed in whole numbers or decimals.

Click on the graphic to see larger view.

The graphic represents an idealized timeline based on the processes used in the U.S. Tsunami Warning Centers. Each Tsunami Warning Center may perform individualized processes within the context of this idealized view, based on the specific event.

Are you ready to engage with your partners in a tsunami event? Click the button below to open a new tab where you will begin the fictional exercise. As you submit your answers, the correct answers will be highlighted in green.

Summary of Promising Practices

Research has shown that effective communication of warning messages have specific components of both style and content:

|

Style |

Content |

|

Clear: Simply worded is best Specific: Communicate the official TWC product information for locations in your area of responsibility Accurate: Errors cause confusion Certain: Authoritative and confident Honest: Convey what you know and don’t know |

Audience-appropriate: Do not use overly technical language or jargon; avoid acronyms Consistent: Internally and externally

As applicable, present information in linear and chronological order Stay in your lane: Provide tsunami details derived from TWC messages only and use the corresponding calls-to-action

|

The following tabs show a couple of effective tsunami communication examples via social media.

Example 1

Example 2

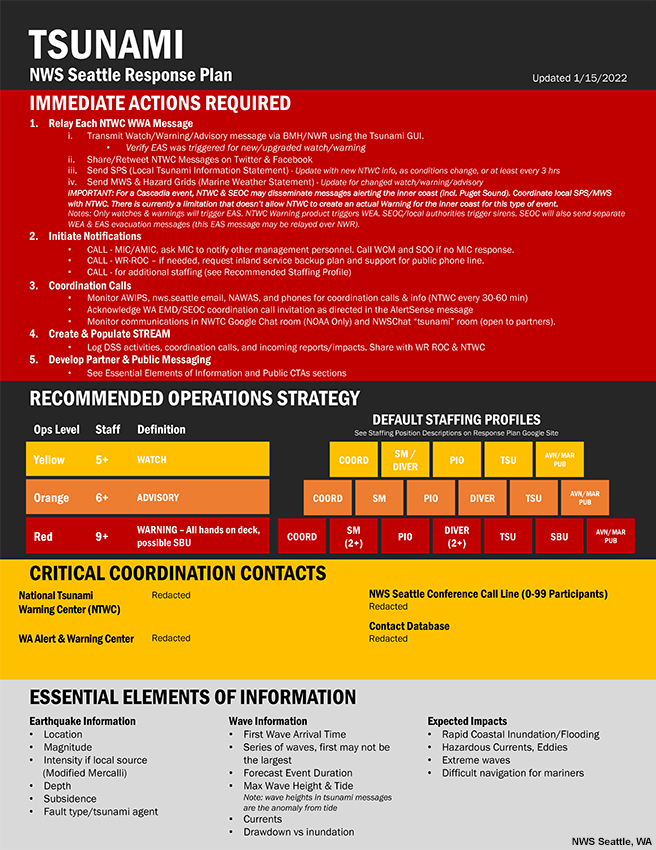

It is highly recommended that coastal National Weather Service forecast offices develop a Response Plan that outlines the operational strategy, contact information, and best communication practices during a tsunami event. For example, see the Response Plan below from the NWS Seattle WFO. In the Seattle office, an event coordinator (COORD), social media officer (SM), communications person (Public Information Officer), tsunami operator (TSU), dissemination & verification (DIVER), and service back-up liaison (SBU) to another WFO are designated in the case of a tsunami event. You may adopt a similar plan for your own WFO by using WFO Seattle’s Response Plan as a template.

Response Plan - Pg. 1

Response Plan - Pg. 2

Local officials interested in becoming TsunamiReady with strategies for streamlining their implementation of mitigation, preparedness, and response strategies can review the COMET lesson TsunamiReady: Guidelines for Mitigation, Preparedness, and Response.

References

U.S. Tsunami Warning System: tsunami.gov

International Tsunami Information Center (ITIC): http://itic.ioc-unesco.org/index.php

National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program (NTHMP): https://nws.weather.gov/nthmp/

COMET lessons available on MetEd:

Contributors

COMET Sponsors

MetEd and the COMET® Program are a part of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research's (UCAR's) Community Programs (UCP) and are sponsored by

- NOAA's National Weather Service

(NWS)

with additional funding by: - European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT)

- Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC)

- NOAA's National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS)

- NOAA's National Geodetic Survey (NGS)

- National Science Foundation (NSF)

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO)

To learn more about us, please visit the COMET website.

Project Contributors

Project Lead

- Vanessa Vincente — UCAR/COMET

Instructional Design

- Amy Stevermer — UCAR/COMET

- Vanessa Vincente — UCAR/COMET

Science Advisors

- Mike Angove — NOAA/NWS Tsunami Program Branch Director

- Christa von Hillebrandt — International Tsunami Information Center, Caribbean Office (ITIC-CAR)/NOAA/NWS Caribbean Tsunami Warning Program

- Dr. Laura Kong — International Tsunami Information Center (ITIC)

- Dr. Charles (Chip) McCreery — NOAA/NWS Pacific Tsunami Warning Center

- Cindi Preller — NOAA/NWS Pacific Tsunami Warning Center

- Ian Sears — NOAA/NWS Tsunami Program Coordinator

- David Snider — NOAA/NWS National Tsunami Warning Center

- Reid Wolcott — NOAA/NWS Seattle, Washington Weather Forecast Office

Other Contributors

- Hannah Cleverly — Director of Emergency Management for Grays Harbor County, WA

Program Oversight

- Amy Stevermer — UCAR/COMET

Graphics/Animations

- Steve Deyo — UCAR/COMET

Multimedia Authoring/Interface Design

- Gary Pacheco — UCAR/COMET

COMET Staff, July 2022

Director's Office

- Dr. Elizabeth Mulvihill Page, Director

- Dr. Wendy Gram, Deputy Director

- Dr. Paul Kucera, Assistant Director International Programs

Business Administration

- Lorrie Alberta, Administrator

- Beth Boddie, Administrative Assistant

- Tara Torres, Program Coordinator

IT Services

- Bob Bubon, Systems Administrator

- Joey Rener, Software Engineer

- Malte Winkler, Software Engineer

Instructional Services

- Dr. Alan Bol, Instructional Designer/Scientist

- Keliann LaConte, Instructional Designer

- Tracy Martinez, Instructional Designer

- Sarah Ross-Lazarov, Instructional Designer

- Tsvetomir Ross-Lazarov, Instructional Designer

International Programs

- Kathryn Payne, Project Manager

- David Russi, Translations Coordinator

- Martin Steinson, Project Manager

Production and Media Services

- Steve Deyo, Graphic and 3D Designer

- Dolores Kiessling, Software Engineer

- Gary Pacheco, Web Designer and Developer

- Tyler Winstead, Web Developer

Science Group

- Patrick Dills, Meteorologist

- Bryan Guarente, Instructional Designer/Meteorologist

- Adam Hirsch, Meteorologist

- James Russell, Meteorologist

- Lee-ann Simpson, Meteorologist

- Andrea Smith, Meteorologist

- Brianna Smith, Meteorologist

- Amy Stevermer, Scientist/Instructional Designer

- Vanessa Vincente, Meteorologist

NOAA/National Weather Service - Forecast Decision Training Division

- Kevin Scharfenberg, Division Chief

- Jason Jordan, Instructor

- Brian Motta, Satellite Training

- Dr. Robert Rozumalski, SOO Science and Training Resource (SOO/STRC) Coordinator

- Ross Van Til, Meteorologist

- Shannon White, AWIPS Training