Produced by The COMET® Program

Landscapes Obliterated

Tsunamis can create a trail of destruction that leaves permanent scars. They can destroy buildings, devastate the landscape, and ruin natural and agricultural lands.

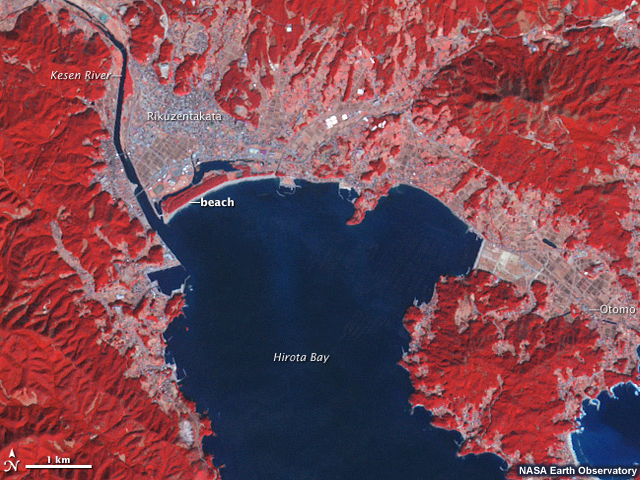

In these images from the Japanese tsunami of 2011, you can see how the tsunami inundated fields, leveled buildings, and carried debris as far inland as the town of Otomo on the right.

Before

After

In this pair of images from the 1998 Papua New Guinea tsunami, you can see how the waves completely wiped away a church.

Here you can see the Scotch Cap lighthouse as it looked prior to April 1, 1946. The white reinforced-concrete tower rose nearly to 30 meters on a bluff 12 meters above the sea.

Early on the morning of April 1, a 30-meter wall of water struck the lighthouse, leaving little but the foundations and a field of rubble.

But tsunamis and their accompanying earthquakes can leave even longer lasting scars.

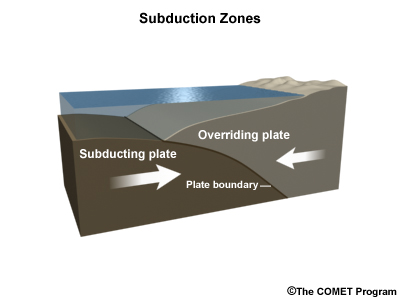

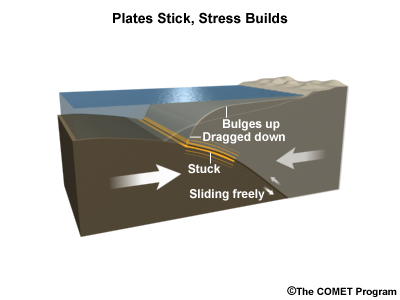

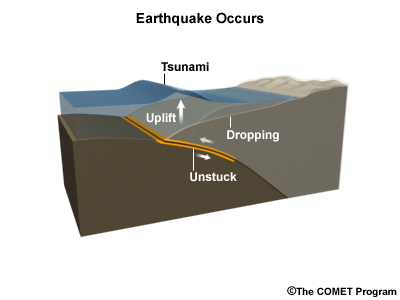

When thrust faults at subduction zones rupture, they can dramatically change the land.

The overriding plate can bend like a bow before the quake when the plates are stuck, but during an earthquake, the portion of the plate nearest the fault springs up while the land immediately behind it drops down.

This effect can be large, and can make coasts even more vulnerable to tsunamis when land sinks, as happened in the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

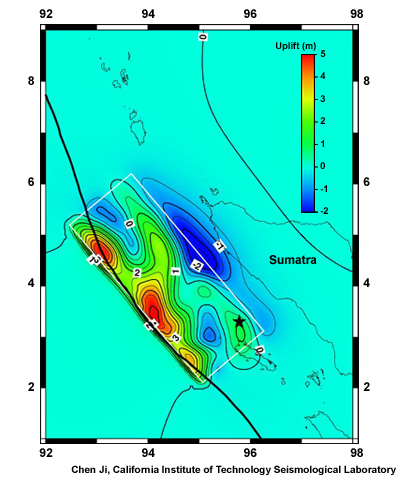

Plate uplift and downdrop around the epicenter of the Indian Ocean Tsunami

In this image from the Indian Ocean Tsunami, you can see how the plate rose near the boundary (thicker black line), shown in reds and yellows, and sank farther behind it, close to shore, shown in blues.

Habitats Changed

Where uplift or down-drop happens, coastlines can either advance or retreat by several hundred meters, either making new land or giving more land up to the sea.

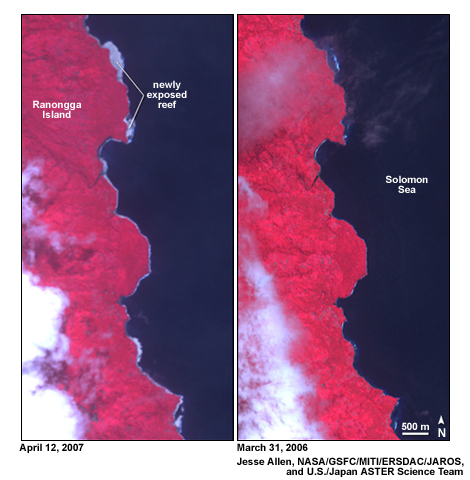

Exposure of the reef around Ranongga Island in the Solomon Islands after a 2007 earthquake lifted the land. (Note: the aftermath image is on the left)

In the tropics, salt water-dwelling mangrove forests and coral are often the organisms that suffer when land is raised, as you can see here on the coast of Ranongga Island in the Solomon Islands before and after a magnitude 8.1 earthquake raised the coast in 2007. With time, new land will form on the newly exposed reef. Sinking land can also produce some interesting side effects.

At one place in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, where the coast dropped after the 2004 earthquake, villagers began noticing mangrove mud lobsters had migrated into their vegetable gardens from the mangrove forests at the coast.

Both in the tropics and elsewhere sinking land often produces ghost forests when tree roots are killed by drowning. This happened in Alaska after the Good Friday Earthquake and Tsunamis of 1964.

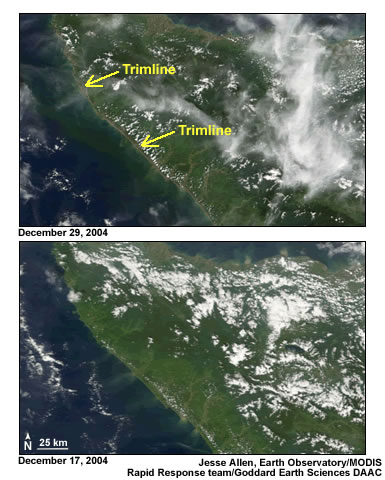

A trimline -- or deforested area -- revealed in the thin brown line along the coast the coast of Sumatra in the top image, was created by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.

Massive waves may also shear off trees, creating a distinctive "trimline" that takes years to reforest, like this one in Sumatra after the Indian Ocean tsunami.

Agriculture Threatened

Farm fields before the 1960 Chilean earthquake

In cases where seawater sweeps over farm fields, the soil grows saltier.

Farm fields inundated by a tsunami and land subsidence after the 1960 Chilean earthquake

The damage to soil is twofold: salt water gets into the soil, and salty sand or clay from the sea is deposited on top of the soil. The longer tsunami waters sit on the land, the worse the damage will be.

Summary

Tsunamis can leave permanent scars where infrastructure and landscapes are scoured.

When land is uplifted or dropped down, coastline locations change. These changes alter the landscape in numerous ways, by exposing coral reefs, submerging tree roots, or causing coastal creatures to migrate inland.

Tsunami-flooded farm fields will have saltier soil from the seawater itself as well as from deposits of salty clay or sand. The longer the seawater covers the land, the worse the damage will be.

Click here to return to the 6+ Hours Page.