In Depth

Coastal Upwelling

When winds blow with persistence over an ocean surface, the Coriolis force acts to move surface water at an angle to the wind direction: to the right in the northern hemisphere and to the left in the southern hemisphere. When winds push water offshore, cold water rises from beneath to replace it. This upwelling substantially reduces sea surface temperatures, which in turn reduces temperatures in the marine boundary layer.

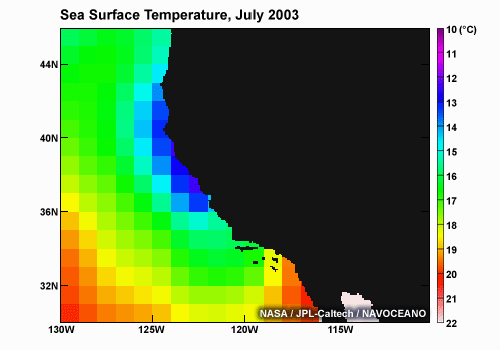

The presence of deep water close to shore enhances the cooling effect of upwelling. This results from deeper, colder water rising to the surface during upwelling. Thus, coastal areas with a narrow continental shelf or where a submarine canyon comes close to shore experience more cooling during upwelling than areas with a broad, shallow continental shelf. This map shows the bathymetry of the central California coast near Monterey. Note the deep canyon that approaches the coast and the relatively narrow continental shelf throughout the region. This area is well know for cool sea surface temperatures, as is shown in this plot of sea surface temperatures for July, 2003 (below).