Growth Trends and Their Impacts

Current Population Trends

Before we take a look at how our built environment has evolved, let's look at current growth patterns in the U.S. What are current growth rates? Where have we traditionally set up our homes and businesses? Where has man's built environment had the greatest impact on the natural environment?

Question 1

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2006 the U.S. population was over 300 Million. What is the projected population for 2040?

The correct answer is c.

Please continue watching the video above.

The U.S. population is growing and changing rapidly.

Our population has grown by leaps

and bounds over the last century -- from seventy six million in the year nineteen hundred to

over two hundred eighty two million in the year two thousand.

In two thousand and six, we passed the three hundred million mark. And we are on our way to four hundred million by two thousand forty.

That's unprecedented growth.

Question 2

In 2006, what percentage of the U.S. population is estimated to live in a metropolitan area?

The correct answer is d.

Please continue watching the video above.

Currently, eighty three percent of us live in urban or metropolitan setting. Urban populations, too, are soaring: among metro areas of one million plus residents, six grew by more than thirty percent in the nineteen nineties; sixteen grew by more than twenty percent and thirty one grew by more than ten percent.

Where We're Growing

So where is most new development happening? Are we filling up the last of our open spaces and farm lands?

In the lower forty eight states, many of our metropolitan areas are located along our roughly twelve thousand miles of coastline, including the Great Lakes. About fifty percent of our population lives within fifty miles of a seacoast. Many of these areas are vulnerable to severe weather events like tropical storms and hurricanes. And if climate change produces higher sea levels, the risk to coastal dwellers will only increase.

There are, of course, large inland metropolitan areas as well. Many of these areas are also growing quickly and face their own challenges.

Phoenix and Las Vegas, for instance, are two of the fastest growing cities in the U.S. Both are in arid locations where future water supplies are a concern. Scientists studying climate change predict that many regions of the southwest will be subject to more frequent and more intense drought.

Current Development Patterns

An increasing population isn’t the only concern. Equally worrisome are the development patterns that come with it.

Question

Which is growing more rapidly? Our population or the rate of land consumption used for development?

The correct answer is b.

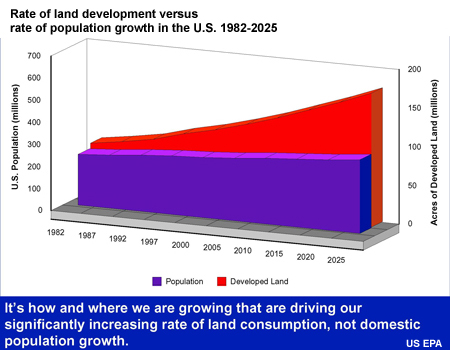

The rate of land conversion for development is currently twice that of our population growth.

Please continue watching the video above.

Nationally, we're consuming land at twice the rate of population growth. But many places continue to sprawl despite little or no population growth. For instance, between nineteen fifty and nineteen ninety, Pittsburgh's urbanized area grew twenty-one times faster than its population!

It has been four hundred years since Europeans began settling the continent, yet a third of all developed land has been built on in just the last twenty-five years.

Since World War II, development has consumed more and more land as nearly everything has gotten bigger – houses, yards, grocery stores, big-box malls, and parking lots. In nineteen twenty, the average density of all developed areas was nearly ten people per acre; by the year two thousand, that had dropped to three point seven five people per acre.

This inefficient land use is taking its toll through habitat fragmentation, loss of farm land, and degradation of our water resources. Our increased dependence on automobiles and highways and an increase in the amount of energy used to heat and cool our large homes lead to emissions of greenhouse gasses and contribute both to micro-climate alterations locally and climate change globally.

Spreading buildings and pavement over large areas also can exacerbate what is known as the “urban heat island effect": a local rise in temperature and air pollution in heavily built cities.

So how has growth and development impacted our lives? Where are we heading in terms of our quality of life and vulnerabilities to weather events? Anyone who flies across the country, looks out the window, and notes the vast stretches of farm and undeveloped land interspersed by tiny towns and cities could be misled to think there is more than enough land for development, farming, and natural habitat. The trouble is, most of the best spots have been found and developed. Population settles where there is a water supply, fertile land, negotiable terrain and tolerable climate. The country’s most productive farmland tends to be just outside of metro areas – and as such it is at risk of being gobbled up for development. Much wildlife, too, is concentrated in these zones.

We still have lots of wild lands in the United States to enjoy, but it will take a concerted effort to protect the places that are most suited to sustain life – including ours. Fortunately, as we’ll learn later in this course, we now understand a lot more about how to grow in ways that benefit both people and the natural environment -- and many communities are acting on this information.

Evolution of Metro Growth and Development

Industrialization and Urban Growth

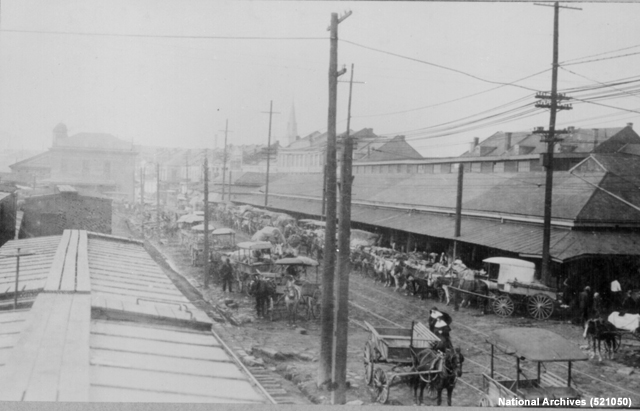

Let's take a look at how urban growth patterns evolved in the United States starting in the late eighteen hundreds.

The rapid industrialization of the 19th century—the steam age—led to the building of factories in many cities. Train lines were built to feed the factories with raw materials. The trains also brought people from the countryside to work in those factories.

Life near the factories was not very pleasant. Pollution, noise, and crowding were the norm. For the more well-to-do, the steam locomotive provided an escape and created the first set of commuters. Trains permitted the development of commuter suburbs. Villages like Brookline, Massachusetts and Bronxville in Westchester County, New York, were built to serve affluent citizens escaping the pollution and crowding of the industrial city. By nineteen twenty, Grand Central Station in New York was handling six hundred and eighty commuter trains per week.

Question

In the late 1800's what do you think led to the spread of cities to more outlying areas?

The correct answer is d.

Please continue watching the video above.

The phenomenon we know as suburbanization – the expansion of a city through the development of surrounding “bedroom” communities – became truly possible with the advent of the streetcar, the first light-rail commuting platform.

The earliest version of the streetcar was the cable car, which appeared in the eighteen eighties and unleashed suburban development in Chicago, San Francisco, and Philadelphia. The cars were moved by a continuously circulating cable, an energy-intensive method that was quickly replaced by the electric streetcar.

Frank Julian Sprague developed the first electric trolley system in Richmond, Virginia, in

the late eighteen eighties. By eighteen ninety three, there were more than two hundred and

fifty electric railways in the U.S.

Compared to the horse and carriage, folks could now zip between home and work. Streetcars could hit speeds of up to twenty miles per hour. Development changed too. Department stores began to locate at the intersections of trolley routes, where suburb and city dwellers alike could reach them. Along trolley lines’ outer reaches, suburban enclaves popped up with homes tailored to the middle class. Atlanta’s Inman Park, for example, was that city’s first streetcar suburb -- just three miles from downtown.

Rise of the Suburbs and the Automobile

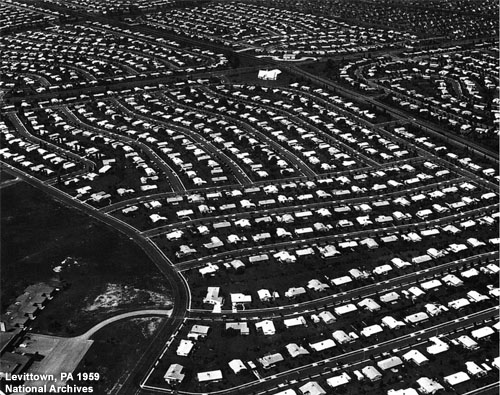

World War II marked a turning point in the way cities were built. The changes were in part a reaction to what cities had become after rapid industrialization, the Depression of the nineteen thirties, and the war years. This was a time of serious housing shortages, crowded conditions and decay as most resources and investment went toward the war effort. War workers and veterans lived doubled up with relatives and friends, or in rooming houses or even cars.

When the war ended and resources were again freed up, the country embarked on massive automobile-oriented suburbanization. Home loans were backed by the Federal Housing Authority and the Department of Veterans Affairs with requirements that favored new single family homes in the suburbs and disfavored houses, townhouses and apartments in the city.

The mass-production lines honed during the war effort shifted focus to mass-producing houses, as in Levittown, the first quintessentially modern suburb. Uniformity became the norm.

In the nineteen fifties and sixties, the “sitcom suburbs”—like those in 'Leave it to Beaver' and 'Ozzie and Harriet'—featured small houses of about nine hundred square feet for returning vets and their families.

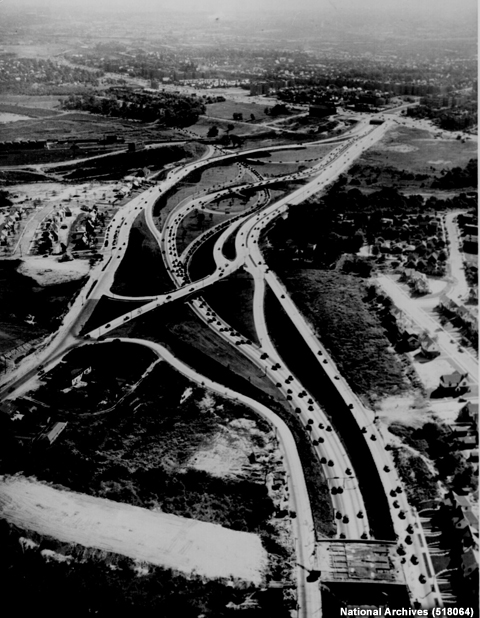

Then in nineteen fifty-six, the Interstate Highway Act provided huge financial support for building commuter freeways, further fostering the development of suburbs.

Question

The 1956 Interstate Highway Act provided funding to build highways across the United States. How many miles make up that system today?

The correct answer is b.

The original Highway Act limited the system to 41,000 miles. Over time, it's been amended to 43,000 miles. The miles that have been built beyond that have been funded by money from sources other than the Interstate Construction funds.

Please continue watching the video above.

The traditional city became so out of favor as a place to live that the federal government began promoting an approach to zoning that made building in the traditional city pattern essentially illegal. The functions of the city were pulled apart and scattered. Housing subdivisions were in separate zones from shops and office buildings, so that the only way to meet one’s daily needs was to travel by automobile.

In the nineteen seventies, jobs began moving out to the “bedroom” communities in a big way, as many metro areas completed peripheral beltways or “by-passes”. These became the second-generation post-war suburbs.

Developers built suburban office parks and malls at the intersections of the new freeways. These became the unwalkable “downtowns” of new “edge cities”. The Perimeter Center area in Atlanta is a quintessential example, in both form and oxymoronic name.

Today only one-fifth of the jobs in metropolitan areas are located within three miles of traditional downtowns, while thirty five percent of metro jobs are located more than ten miles away from city centers.

Technology's Impact: AC and the South

The automobile isn’t the only invention that has altered U.S. growth patterns. Two others have also profoundly changed the country: air conditioning and central heating. Their use allows us to essentially ignore the weather and live and work in relative comfort wherever we desire. In the summer, the southeastern states are tremendously hot and sticky, but air conditioning opened the south to those who enjoy mild southern winters but still want to live in comfort during the summer.

Air conditioning has been around far longer than the post-World War II housing boom. Some ancient Roman homes had circulating water systems in their walls to cool adjacent rooms. Modern air conditioning was born in the 1840's, when a doctor in Florida, Dr. John Gorrie, used compressed ammonia and its chilling effect to create ice. He then used the ice to cool his patients' rooms. By 1902 the first large air conditioning units were developed by Willis Haviland Carrier to cool workplaces. But it wasn't until 1947 that mass manufacturing of air conditioning units brought the price within reach of most middle class Americans.

That was a clear boon for the South. Since 1940, eight of the 10 fastest growing cities in the U.S. are located in the southern parts of the country. Many demographers believe that this growth was substantially enabled by air conditioning.

But what's good for our daily comfort is not necessarily good for the environment. Air conditioning units use a lot of energy. Despite government-mandated increases in the efficiency of air conditioning units, their expanded use has increased household electricity consumption. One study found a two hundred seventy-one percent increase in the number of houses with central air from nineteen seventy-eight to nineteen ninety-seven, and a corresponding thirty-five percent increase in average household electricity consumption. Fifty-five percent of households – 48 million in all – had air conditioning.

With growing concern over the release of greenhouse gasses from power plants, we will need to find ways to reduce our use of air conditioning through smarter architectural design and better insulating building materials.

Social Trends

Technology has certainly played an important role in our growth patterns. But social trends also play a large role. In our current, third-generation, suburbs our houses have been getting bigger, growing from an average of fourteen hundred square feet in nineteen seventy to two thousand square feet the year two thousand. Bigger homes require more energy to heat and cool their large interiors, increasing their contribution to greenhouse gasses.

Houses aren’t the only structures that have grown in size and energy requirements. Modern big-box stores can cover two hundred thousand square feet and fill twenty acres when parking is included. Today's large "supercenters" are eighty thousand square feet larger than stores of just ten years ago.

Question

How long is your daily commute to work? Enter the amount of time you need to travel to get from home to work.

Here's how you're commute compares to the average. Several polls conducted since 2005 show the average commuter spending around 25 minutes getting to or from work.

We also like our big backyards which means building new homes on undeveloped land further and further out from city centers. People living in newer, more spread-out areas drive up to forty more miles a day than their counterparts in more traditional settings. And as congestion grows, the time this driving takes is growing even more rapidly. The typical American mom sometimes spends more time driving in traffic-clogged streets than she does in childcare or conversation.

More recently, many communities have begun to recognize that these patterns are unsustainable. As congestion grows, more people are trading yard and home size for a chance to live closer to city centers, nearer to jobs and activities. At the same time, demographics are changing: increasingly, there are more empty nesters than parents with young children, the classic suburban homebuyers. Cultural norms are shifting, too, so that cities are becoming more popular. And overshadowing all this are concerns over energy security, gas prices and global warming, which make a driving-intensive society more vulnerable.

As we continue to evolve our built environment, it only makes sense to adapt our behaviors and design decisions to reduce our impact on the environment and improve our quality of life. The rest of this course shows how our built environment impacts the local watershed and the air we breathe, how this in turn presents health and safety issues, and suggests ways that we can reduce our impact.

Take Aways and References

Story Ideas

The following are suggestions to develop viewer segments related to this unit's content.

Land Preservation and Development Patterns

What are some of the more valued lands in your region? Interview a local land steward and discuss the land's value in terms of recreational, ecosystem and watershed management.

Are building lots in your area getting larger or smaller? What are the current trends in lot size in new developments? Talk to local zoning boards or developers and discuss the pros and cons of large versus smaller lots.

How about the trend in the size of new homes? What's the trend in new developments in your area? Are there more stand-alone homes or town homes and condominiums? What's the average size of new stand alone homes? Interview new home owners and share their opinions on the size of their new dwelling.

Transportation and Commuting

What are average commute times in your area? Consult the U.S. Census Bureau's 2005 report to find numbers for your city (http://www.census.gov/acs/www/Products/Ranking/2003/pdf/R04T160.pdf). Interview a variety of commuters - from car drivers, bus riders and bicyclists- to share their thoughts on their commute.